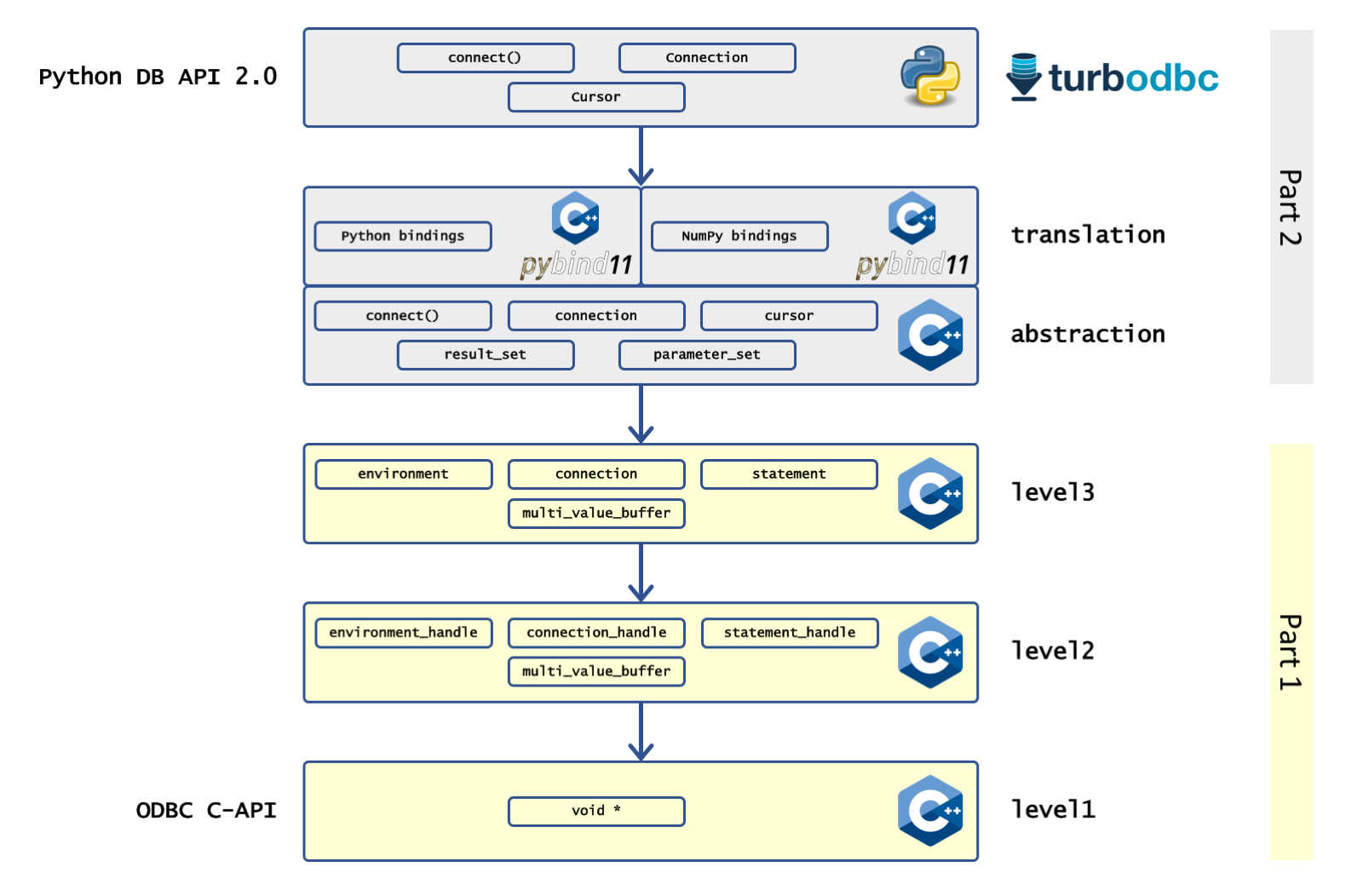

In the first part of this series, we learned how turbodbc builds a few layers of C++ code on top of the open database connectivity (ODBC) C API. We ended up with a reduced API that improves on its foundation by introducing resource management, better types, exceptions, and making a few decisions for us. Still, our C++ API is pretty close to the C API, meaning we have notions of environments, connections, statements, and buffers. The Python database API 2.0 has a different, more usable concept in that it only knows connections and cursors. Python knows nothing about buffers, environments, and the like; it expects the driver to handle these things internally.

In this second part of our two-part series, we explain how to approach the desired Python API from the C++ side, how to establish a C++/Python conversion layer, and how to apply finishing touches in pure Python. The procedure presented here is rather generic and may serve as an example to use other C++ libraries from Python, even if ODBC is not on your radar.

Result sets and parameter sets

Python’s DB API version 2.0 offers the cursor abstraction of which the main methods are execute() and executemany(). Both methods can execute arbitrary queries and commands with one or more (executemany) sets of parameters. If they exist, results are then retrieved using the fetch() method or one of its variations. Both execute() and fetch() constitute the main challenges in bringing ODBC to Python. The C++ classes we have created so far have very different low-level semantics compared to the high-level classes and methods we will eventually require. In order to make the transition to Python easy, we develop an additional C++ layer targeted at bringing the API closer to what Python users would expect. Building on top of the statement object we came up in the first part of our series, we create a dedicated [result_set](https://github.com/blue-yonder/turbodbc/blob/master/cpp/turbodbc/Library/turbodbc/result_sets/result_set.h) interface (and two implementations with synchronous and asynchronous I/O) with the following responsibilities:

- Handle all bookkeeping involved with batched data transfer.

- Determine the best data transfer type for any given column in the result set. The transfer type determines how the bytes written to buffers need to be interpreted.

- Determine the number of rows to transfer in each batch of the result set. It is important to find a balance between memory footprint (small buffers) and minimizing database roundtrips (large buffers).

-

Create buffers and bind them to the result set. Similarly, we create a parameter set with the following responsibilities:

- Handle all bookkeeping involved with batched data transfer.

- Determine the best transfer type for the values associated with a specific parameter. This is a surprisingly difficult task, since databases are often less than helpful in reporting the appropriate type.

- Modify transfer types when a new parameter set has different value types than the previous ones. This is an unfortunate possibility we have to deal with because the Python database API 2.0 says that the user is allowed to do so.

- Create appropriate parameter buffers and bind them to the statement. These high-level abstractions allow us to build C++ classes and functions which are already very close to the Python database API 2.0.

Exposing classes and functions

Up to this point, we are still firmly rooted within the C++ world. We need a translation layer with the following responsibilities:

- Expose relevant C++ classes and functions so that they can be used from Python.

- Translate result set data to Python objects of appropriate types.

- Translate Python objects passed as parameters to

execute()andexecutemany()to parameter types the ODBC API understands. The pybind11 library helps with most of these responsibilities. The following code is a good example of exposing the C++ classconnectionto Python under the nameConnection:

pybind11::class_<turbodbc::connection>(module, "Connection")

.def("commit", &turbodbc::connection::commit)

.def("rollback", &turbodbc::connection::rollback)

.def("cursor", &turbodbc::connection::make_cursor);

This snippet exposes a total of three methods, but omits an __init__() method. We do this because we do not require Python users to create connections by using the initializer. Rather, they are supposed to use the connect() function that is required by the Python database API 2.0 and that we also need to expose:

module.def("connect", turbodbc::connect);

Translating result sets and parameters

Pybind11 also helps with the translation of data. For example, pybind11 automatically translates Python unicode strings to C++ strings or C++ integers to Python integers. The translation of result sets and parameters, however, requires a little extra work. Consider the case where a column of a result set is read from a database. The database’s ODBC driver stores ten values as binary data in a buffer provided by turbodbc. Pybind11 cannot know how to interpret such binary data out of the box. To help pybind11 make sense of the bits and bytes, one could introduce a custom conversion of binary data to a type-safe discriminated union container such as the boost::variant<> or C++17’s std::variant<> templates. For these types, converters could be defined so pybind11 knows how to translate them. However, this process would require two conversion steps; one into an intermediate format with built-in type information and the final one to Python. To avoid the performance penalty of such a double-conversion, turbodbc features custom code to convert binary data retrieved from the database to Python objects directly:

pybind11::object make_object(turbodbc::type_code code, char const * data_pointer, int64_t size)

{

switch (code) {

case type_code::boolean:

return pybind11::cast(*reinterpret_cast<bool const *>(data_pointer));

case type_code::integer:

return pybind11::cast(*reinterpret_cast<int64_t const *>(data_pointer));

case type_code::floating_point:

return pybind11::cast(*reinterpret_cast<double const *>(data_pointer));

case type_code::string:

return pybind11::reinterpret_steal<object>(PyUnicode_FromString(data_pointer));

case type_code::unicode:

return pybind11::reinterpret_steal<object>(PyUnicode_DecodeUTF16(data_pointer, size, NULL, NULL));

case type_code::date:

return pybind11::make_date(*reinterpret_cast<SQL_DATE_STRUCT const *>(data_pointer));

case type_code::timestamp:

return pybind11::make_timestamp(*reinterpret_cast<SQL_TIMESTAMP_STRUCT const *>(data_pointer));

default:

throw std::logic_error("Encountered unsupported type code");

}

}

This function uses the type flag code to convert binary data represented by data_pointer to a Python object, and thus avoids an intermediate conversion layer.

Since data scientists are among turbodbc’s key target audience, turbodbc further provides efficient converters that create NumPy arrays. In contrast to traditional Python lists of objects, NumPy arrays store data in a contiguous binary formats. Since the binary representations of integers and floating point numbers are the same in both ODBC API and NumPy, the conversion is little more than copying memory blocks around, rendering the process extremely efficient.

Finishing touches

With the C++ classes and functions exposed to Python, the main work is done. Users can leverage this interface to query the database. However, the interface our C++ library provides is not the interface required by the Python database API 2.0 specification.

To really implement the specification, we add another level. However, this level is entirely written in Python and has the following responsibilities:

Translate custom C++ exceptions to proper Python exceptions that are part of Python’s standard exception hierarchy. Create connection strings based on keyword arguments. Manage preparing statements, passing parameters, and executing commands. Provide constants and types required by the API specification. For example, the execute() method uses calls to a cursor-like object called self.impl that is exposed from C++:

@translate_exceptions

def execute(self, sql, parameters=None):

self._assert_valid()

self.impl.prepare(sql)

if parameters:

buffer = make_parameter_set(self.impl)

buffer.add_set(parameters)

buffer.flush()

self.impl.execute()

self.rowcount = self.impl.get_row_count()

cpp_result_set = self.impl.get_result_set()

if cpp_result_set:

self.result_set = make_row_based_result_set(cpp_result_set)

else:

self.result_set = None

return self

It may be counterintuitive to have a Python layer on top of our C++ library that is already exposed to Python. The reason behind this is purely pragmatic: It is much faster (development-wise) to get some things done in Python than in C++. Hence, things that are trivial to do in Python were done in this language. The C++ layer was developed right until the point where nasty low-level details were safely dealt with.

Conclusion

Over these last two posts, I demonstrated how to transform a low-level C API into a high-level Python package. Even if you do not care about ODBC in general or turbodbc in particular, you should take home the following points:

Do not call stateful C APIs with side effects directly. Instead, create an interface to closely match the API. This helps with unit testing since it facilitates mocking. Improve on the C API by elevating the contained concepts to proper classes and data types. Add exception handling and get rid of pointers. Implement those parts of your envisioned Python API in C++ that require operations that are hard to do in Python (efficiently or elegantly). Keep this layer as small as possible. Expose C++ classes and functions to Python. Use the exposed units in a final Python layer. This layer should implement the user-visible API and generally do everything that is easy to do in Python. Thanks for reading, have a look at turbodbc’s GitHub page and follow the latest developments on twitter.