Databases are the core of modern information technology. Databases are used by web servers to store content, by businesses to place orders, and by data scientists as their data sources. To give Python users easy database access, the Python community has devised a standard database API that is specified in PEP 249. Turbodbc is an open source project that links the Python database API with another standard database API: open database connectivity (ODBC).

In a perfect world, database vendors (or the open source community) would supply highly optimized Python drivers that conform with PEP 249. With a few notable exceptions, such as the fantastic asyncpg module, this rarely happens. Considering the rising number of non-esoteric programming languages, this should not come as a surprise given the effort required to build a reliable, fast database driver for just one language. This leaves Python users often stranded with slow native drivers — or no native drivers at all. Enter turbodbc.

Turbodbc allows Python users to hook up with relational databases using ODBC drivers. Written in C, ODBC is a standard API for database communication. Database vendors supply ODBC drivers that translate generic ODBC API calls to database-specific instructions. The great advantage of ODBC is that any application or language that speaks ODBC can communicate with any database for which ODBC drivers exist. Hence, virtually all relational databases ship ODBC drivers.

Turbodbc lets Python users tap into the ODBC ecosystem, opening up new or potentially faster possibilities for database interaction. While it is not the first module to do so, turbodbc significantly improves on speed of earlier packages and uses a modern C++11 backend at its core.

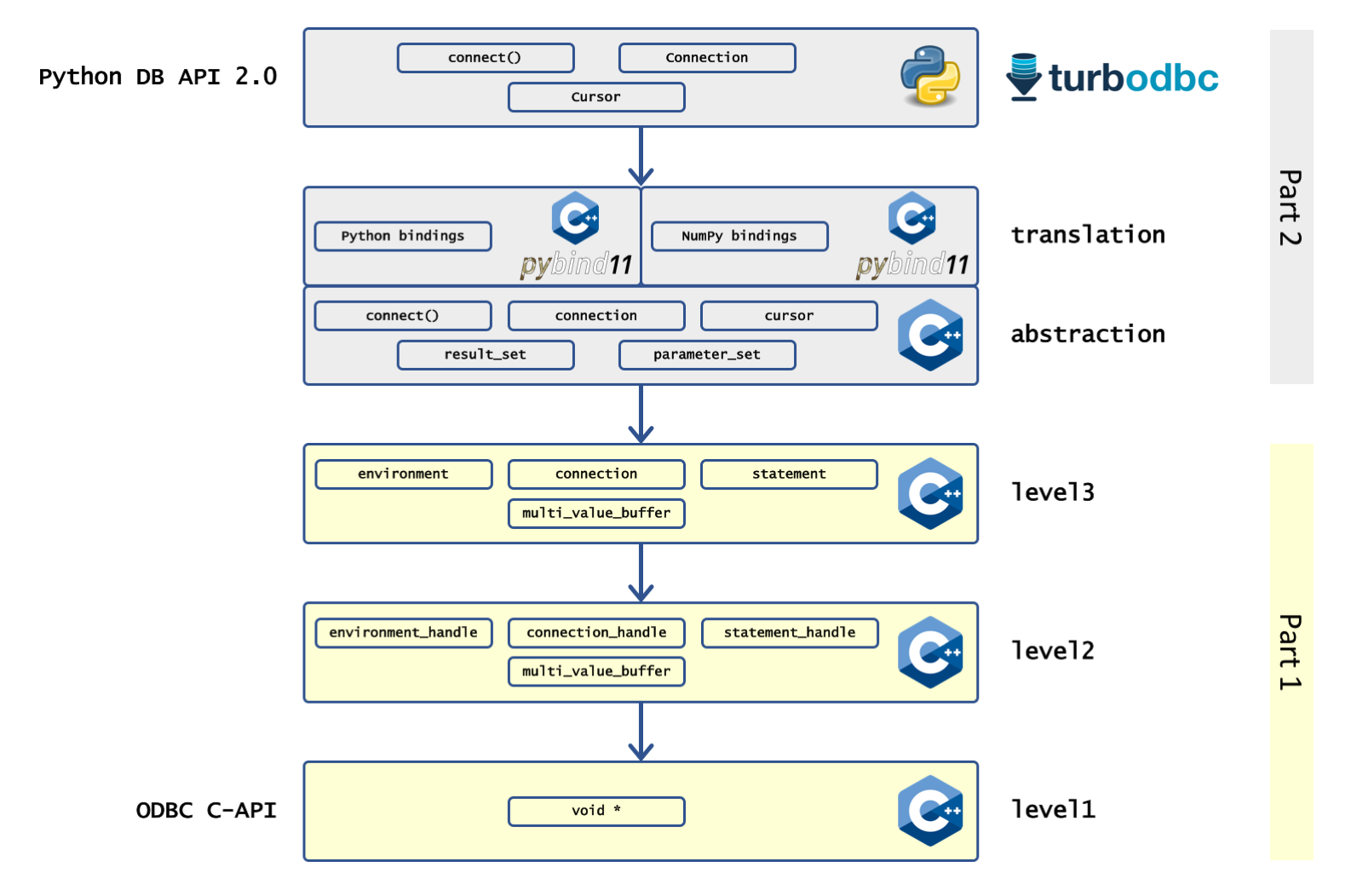

In this series, we are sketching how turbodbc transforms the low-level ODBC API written in C to a high-level Python package. This first of a two-part series focuses on getting a more user-friendly C++ API by wrapping the low-level C API. The second part then shows how to use this C++ API to build a fully functional Python package. [caption id=”attachment_1303” align=”aligncenter” width=”1600”]

An overview of the “Making of Turbodbc” article series, showing the involved layers with their most important concepts[/caption]

The ODBC API

The ODBC API is a collection of standard C header files that contain about 80 C functions plus a myriad of macros defining types and constants for magic numbers. Here is a typical example for one such function:

SQLRETURN SQLBindCol(SQLHSTMT StatementHandle,

SQLUSMALLINT ColumnNumber,

SQLSMALLINT TargetType,

SQLPOINTER TargetValuePtr,

SQLLEN BufferLength,

SQLLEN * StrLen_or_Ind);

All ODBC functions are similar in that they take at least one handle parameter (a pointer to a memory region that stores metadata concerning environments, connections, or statements) and they return a value indicating success, failure, or other states (such as no more data available in a certain result set). This particular function tells the ODBC API that when retrieving result sets associated with the given database statement, it should write data for a given column to particular memory regions using specific data types. In addition to a statement handle, it takes another five parameters:

- An index identifying the column of the result set.

- A magic number that indicates which data type is used to retrieve this column’s data.

- A pointer to a memory block where data is stored. This block typically provides sufficient space for multiple elements corresponding to data of more than one row.

- The size of a single data element.

- A pointer to a memory region that contains metadata on the retrieved data such as string lengths or an indication that specific values are indeed

NULL.

Using the ODBC API basically means managing side effects. Some calls write data to memory regions specified by earlier calls, some calls read data from memory regions specified earlier, other calls manipulate values pointed to by parameters. Most calls require an ecosystem of handle objects and some only work when an actual database connection has been established or other calls have been made earlier in a specific order. All this state makes building anything on top of ODBC less than pleasing. For starters, let us improve on this by making unit testing easy.

A testable base layer

Turbodbc simplifies its unit tests by not using the actual ODBC API in unit tests. Instead, it uses instances of a thin API wrapper:

namespace level1 {

class api {

// ... snip ...

public:

SQLRETURN bind_column(SQLHSTMT statement_handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT target_type,

SQLPOINTER target_value_ptr,

SQLLEN buffer_length,

SQLLEN * length_indicator_buffer) const;

private:

virtual SQLRETURN do_bind_column(SQLHSTMT statement_handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT target_type,

SQLPOINTER target_value_ptr,

SQLLEN buffer_length,

SQLLEN * length_indicator_buffer) const = 0;

};

}

The level1::api class provides an interface (following the non-virtual interface pattern) for child classes to implement. The provided methods match a subset of the ODBC API’s functions exactly, although I have taken the liberty of updating a few function and parameter names. The interface is implemented by child classes such as unixodbc_backend:

SQLRETURN unixodbc_backend::do_bind_column(SQLHSTMT statement_handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT target_type,

SQLPOINTER target_value_ptr,

SQLLEN buffer_length,

SQLLEN * length_indicator_buffer) const

{

return SQLBindCol(statement_handle,

column_id,

target_type,

target_value_ptr,

buffer_length,

length_indicator_buffer);

}

The methods of unixodbc_backend implement the api interface by trivially matching the methods with their real ODBC API counterparts.

So why all the fuss when, in the end, we still call the same old ODBC functions? The benefit lies in the fact that instead of hiding our dependency on the ODBC API in some dusty source file, we can make this dependency explicit by calling methods of a level1::api instance specified by the user. In unit tests, it is a simple matter of passing a mock object created with the googlemock framework instead of “real” unixodbc_backend instances.

Just for the purpose of unit tests, this allows us to ignore call orders and well-prepared handles, as well as allows us to exert the level of control we need to test functions in isolation instead. For example, we can easily “provoke” errors by having mock instances return codes indicating failure every time bind_column() is called.

For the production code, of course, call orders and handles remain important, but they no longer need to be reproduced in every single unit test.

Introducing basic abstractions

The level1::api solves the problem of unit testing, but aside from this, we still have to deal with bare pointers and tons of parameters. Let us stack another layer on top of it that we call level2::api. It has the following tasks:

- Instead of using return codes that indicate failure or success, use exceptions to the same means.

- Instead of modifying values pointed at by function parameters, use return values.

- Instead of using ODBC-supplied handle types (the macros all resolve to

voidpointers), use type-safe data structures. - Use C++ standard types and custom data types to reduce the number of function parameters.

- Replace

voidpointer arguments that may point to either integers or strings depending on the context with overloaded functions for supported types.

The basic interface of this layer looks like this:

namespace level2 {

class api {

// ... snip ...

public:

void bind_column(statement_handle const & handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT column_type,

multi_value_buffer & column_buffer) const;

private:

virtual void do_bind_column(statement_handle const & handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT column_type,

multi_value_buffer & column_buffer) const = 0;

};

}

The signature contains a few noteworthy things. The method no longer has a return code — it is supposed to raise an exception in case of errors. A new statement_handle type replaces the previously used void pointer disguised as the SQLHSTMT macro. Finally, three arguments specifying memory regions are combined to a multi_value_buffer object. Just as level1::api before, level2::api is an interface. This allows tests for higher-level code to mock the level2::api instead of the more cumbersome level1::api.

Obviously, there is an implementation of level2::api that uses an instance of level1::api to elevate its abstraction level. This is what the implementation for do_bind_column() looks like:

void level1_connector::do_bind_column(statement_handle const & handle,

SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT column_type,

multi_value_buffer & column_buffer) const

{

auto const return_code = level1_api_->bind_column(handle.handle,

column_id,

column_type,

column_buffer.data_pointer(),

column_buffer.capacity_per_element(),

column_buffer.indicator_pointer());

impl::throw_on_error(return_code, *this, handle);

In testing this level1_connector, we rely on mock implementations of level1::api created with googlemock. This allows us to test all methods of level1_connector without ever calling the real API or a real database, making it particularly easy to test error scenarios.

Objects and decisions

So far, level2::api is still one big blob of methods with a lot of room for improvement. That is why we built another layer on top of it with the following responsibilities:

- Eliminate handle object parameters by splitting up the single object API to three objects with methods dealing with environment, connection, and statements, respectively.

- Hide functions dedicated to error handling, since error handling has already been taken care of by now.

- Hide initialization and finalization methods in favor of using constructors and destructors following the RAII (resource acquisition is initialization) pattern.

- Where it makes sense, make choices for certain parameters (for example which ODBC version to use) so that these parameters no longer need to be provided externally.

Here is how the statement interface looks like:

class statement {

// ... snip ...

public:

void bind_column(SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT column_type,

cpp_odbc::multi_value_buffer & column_buffer) const;

private:

virtual void do_bind_column(SQLUSMALLINT column_id,

SQLSMALLINT column_type,

cpp_odbc::multi_value_buffer & column_buffer) const = 0;

};

By now, you will not be surprised that there is an implementation which uses the level2::api to do the heavy lifting, and that we use mocks of level2::api to test this implementation. Likewise, mock implementations of the statement interface can be used to test higher-level code.

The story so far

Starting from the original ODBC API, we added three layers of abstractions. The first layer gives us basic testability by introducing an interface class for the ODBC API. The second layer gives us methods that are easier to use by using better parameter types, better return values, and exception handling. The third layer gives us proper objects to work with and also made some decisions for us. This procedure may serve as a template to deal with not just ODBC, but any C API.

Still, even with all our abstractions in place, we are pretty close to the original ODBC API, meaning we have notions of environments, connections, statements, and buffers. Learn how we use these basic components to build a truly high-level Python driver in part 2.