Java: Giants and Infinite Loops

I have an easy-to-code, hard-to-spot, impossible-to-debug infinite loop puzzle for us to solve. To help us see the issue, I also have a small handful of amazing people to introduce who have helped me solve numerous problems. But, first, some introductory quotes:

This should terrify you! – Douglas Hawkins, java JVM and JIT master, while introducing this puzzle.

If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants – Isaac Newton

The first is from a java JVM and just-in-time (aka JIT) compiler master, as quoted from one blurb in a 100+ minute presentation on his area of expertise. The second is from a scientist who himself became a giant whose shoulders uncounted others – famous, incredible others – have stood upon. Both are relevant to this blog, but first the puzzle:

The Seemingly-Impossible Infinite Loop

Let’s start with Hawkins and his “terrifying” situation, who at the time was explaining a trivial-to-code infinite-loop bombshell.

Shared Variables:

Object dataShared = null; //some data that the producer will create.

boolean sharedDone = false; // true only when we have produced dataShared.

Producer Thread:

dataShared = …; // some data is being produced here by the thread

sharedDone = true; //we are done producing so let the consumer make use of it

Consumer Thread:

while ( sharedDone == false); //busy wait spin until producer is finished.

print (dataShared); // executes once sharedDone is set to true by the other thread

The intent is for Consumer Thread to busy-spin while Producer Thread finishes creating dataShared. Once notified that dataShared is ready (via a true value for sharedDone), the consumer will make use of dataShared.

Unfortunately, this is likely to loop infinitely. Do you see the issue? Amazingly, if you create a test program and debug this, you will never reproduce the infinite loop. If you create a trivial test program, you also likely will not reproduce the issue. If you put this into production with real producer and consumer logic, you most likely will reproduce the infinite loop fairly consistently (except this time you were really hoping you would not). What on earth could the issue here be?

This brings me to Newton.

Isaac Newton

Newton’s statement reads like a humble admission but is more accurately a roadmap for success. Brain Pickings has a nice article, Standing on the Shoulders of Giants, on the background of the Newton quote. At the time, the notion that one should study past masters while in pursuit of new knowledge was a minority viewpoint. Somehow the need to rely on others was a bruise to the ego. Newton understood, however, that revolutionary ideas can come from combining existing knowledge from mundane sources. Einstein would later call this creative process “combinatory play”. And, indeed, what Newton produced was truly revolutionary. Let’s take his advice and tour some masters to see if they can help with this puzzle.

Martin Thompson

So, if at first glance the code looks clean then maybe there is something hidden in the hardware architecture. The giant who first introduced me to the great impact of computer architecture on production software is Martin Thompson, as found in a one-hour presentation How to do 100K TPS at Less than 1ms Latency with Michael Barker that is very relevant today despite having been recorded in 2010. Martin Thompson, borrowing a term coined by racing driver Jackie Stewart, explains that you must have some “mechanical sympathy” to understand how to write code that runs well on production-quality hardware. Even if you do not use the software pattern ultimately revealed in this video, the video itself is an excellent display of using mechanical sympathy in software design considerations.

I will pause a moment while you watch the video…. All good? So, having learned all about the hidden magic of CPUs, caches, and main memory, my first educated guess for the infinite loop above is the following: Perhaps we have multiple copies of “sharedDone” in our L1 to L3 CPU core caches. While one CPU’s cache has been set to “true”, perhaps the other may still say “false”. If true, the Consumer Thread, not knowing it has a stale version of the truth, would loop on and on. Is this actually possible?

In my first version of this blog, I thought it was indeed possible for caches to have mismatched information such that they could create an infinite loop. Luckily I asked for a blog review before posting and the person I will properly introduce next disabused me of this idea. Although there is indeed something missing from our code above to prevent the infinite loop, the reason why in this case has nothing to do with hardware. For a given memory location (such as the value of sharedDone), the hardware must give the illusion of a single value across all memory. So, although in reality you may have different values between caches and main memory from time to time, you will never observe this to be true.

Let’s properly introduce our next master.

Aleksey Shipilev

So, if the hardware is happy, is the problem in the java memory model somehow? The next giant on our tour is someone who can speak to that: JVM master Aleksey Shipilev. Just reading through his articles in JVM Anatomy Quarks will amaze you with how much you don’t know you don’t know. See also his widely-used microbenchmark framework JMH. For this specific exercise, we can learn much from another hour-long video titled Java Memory Model Unlearning. Please enjoy.

…Okay, well, if you are like me, you found the start of the video a bit intimidating. However, if you had the patience to get through it, I am sure by the end you appreciated the journey (and the speaker). Hey, he’s a giant – these topics are indeed challenging! As a reward for your patience, you almost certainly now know more about this subject than anyone else at your company – a newly minted giant yourself.

So, now we see we must tell java that more than one thread will be updating and reading this variable by using the keyword “volatile”. With “volatile”, java knows that any changes to “sharedDone” must be instantly published to all threads that can observe this field. This is why you may have already found “volatile” in your career if you have searched for “java double checked locking”. (My favorite Shipilev quote from the video: “If you are not sure where to put volatile, put it freakin’ everywhere!”)

(In fact, Shipilev reminds me that since we only have one variable that requires coherency between the threads, we could technically use “getOpaque()” and “setOpaque()” with “VarHandle” rather than the stronger “volatile”. If you watched his talk, or if you would like to study the Opaque section in Doug Lea’s paper Using JDK 9 Memory Order Modes, which Shipilev pointed me to, you can further appreciate this fine point. Finally, note that Shipilev contributed comments and suggestions to the Doug Lea paper, as did other giants – I find this community of computer scientists so impressive…)

Well, we know how to fix the problem, but do we really understand how the absence of “volatile” creates an infinite loop? If the hardware must give the illusion of a single value across memory, why exactly is “volatile” important? How exactly do all of these concepts Shipilev just taught us really come into play?

Douglas Hawkins

Well, I guess I must give up and return to the person who proposed the puzzle, our giant Douglas Hawkins. Of his many presentations (watch them all!), my favorite is the 100+ minute presentation Understanding the Tricks Behind the JIT where he mentions this specific puzzle. Here, Hawkins gives an expert and entertaining dive into the java just in time (aka JIT) compiler. I will again pause for you to watch it, including minute 54 that sparked this post.

…All done watching? So, now you fully understand the final reason the above will loop infinitely. The code you write, which is compiled to bytecode, is much closer to a “statement of intent” than a specific “mandate” to do exactly what you say. The debugging experience will fool you into thinking every line is executed as-is, in code order. However, in production, this is a lie.

The JIT employs many optimizations as it transforms bytecode to assembler code. By “optimization” the JIT means “I’ll rewrite your code for optimal performance”. One of these optimizations is called “loop invariant hoisting” where a value which cannot change in the current thread can be rewritten as a local constant. If you do not use “volatile”, the JVM assumes that multi-thread situations need not be considered. “Volatile” and “VarHandle” do not exist to tackle issues caused by the hardware. They exist to better inform the JIT optimizer of what it can and cannot do!

So, expanding on the Hawkins video further for this puzzle, we have:

- The Consumer thread code can legally be rewritten by the JIT (in the absence of the “volatile” keyword) as the following:

boolean localDone = sharedDone; // local constant, will never change while ( localDone == false); //infinite spin, clearly localDone is never updated. print (dataShared). //never gonna happen - This rewriting is done by the JIT as it transforms bytecode to assembler at run time, if it so chooses to do this optimization. If sharedDone is false at optimization time, we loop infinitely. If it is true at optimization time, you would probably throw an exception repeatedly while trying to use uninitialized objects (because the Producer actually has not completed).

- When stepping through the debugger, you are stepping over code in “bytecode land” only, not the rewritten assembler. So, this infinite loop is impossible to reproduce in the debugger, and suddenly you are questioning your career choice.

Terrifying? Yes, yes I believe so.

Chris Newland

Our mystery is solved, but the greater lesson here is that the JIT will rewrite your code under high loads for performance, and a “loose understanding” of java coding and memory-model rules can lead to unintended consequences. A great (surprisingly short) article to see JIT rewriting in detail is Shipilev’s first JVM Anatomy Park article Lock Coursening and Loops. But, we can do even better.

A fourth giant related to this discussion is Chris Newland who created the visualization tool JITWatch for you to see your code, the compiled bytecode, and the JIT assembler all in one glorious screen (and more!). With this tool you could verify the infinite loop in the assembly. Enjoy my favorite presentation of his on his tool called Understanding HotSpot JVM Performance with JITWatch.

To really show how different assembly can be from the original, and as an excuse to play with JMH and JITWatch, suppose we have a simpler JMH test program with the following:

@Param("525600")

long answer;

static long howDoYouMeasure_MeasureAYear(

int daylights, int sunsets,

int midnights, long cupsOfCoffee,

int inches, int miles, long laughter, short strife){

int minutes = 525_600; //FYI 0x80520 in hex

long result = daylights + sunsets + midnights + cupsOfCoffee;

result += inches + miles + laughter + strife;

result -= (result - minutes);

return result;

}

@Benchmark

@CompilerControl(CompilerControl.Mode.DONT_INLINE)

public boolean get() {

long result = howDoYouMeasure_MeasureAYear(daylights, sunsets, midnights, cupsOfCoffee,

inches, miles, laughter, strife);

return result == answer;

}

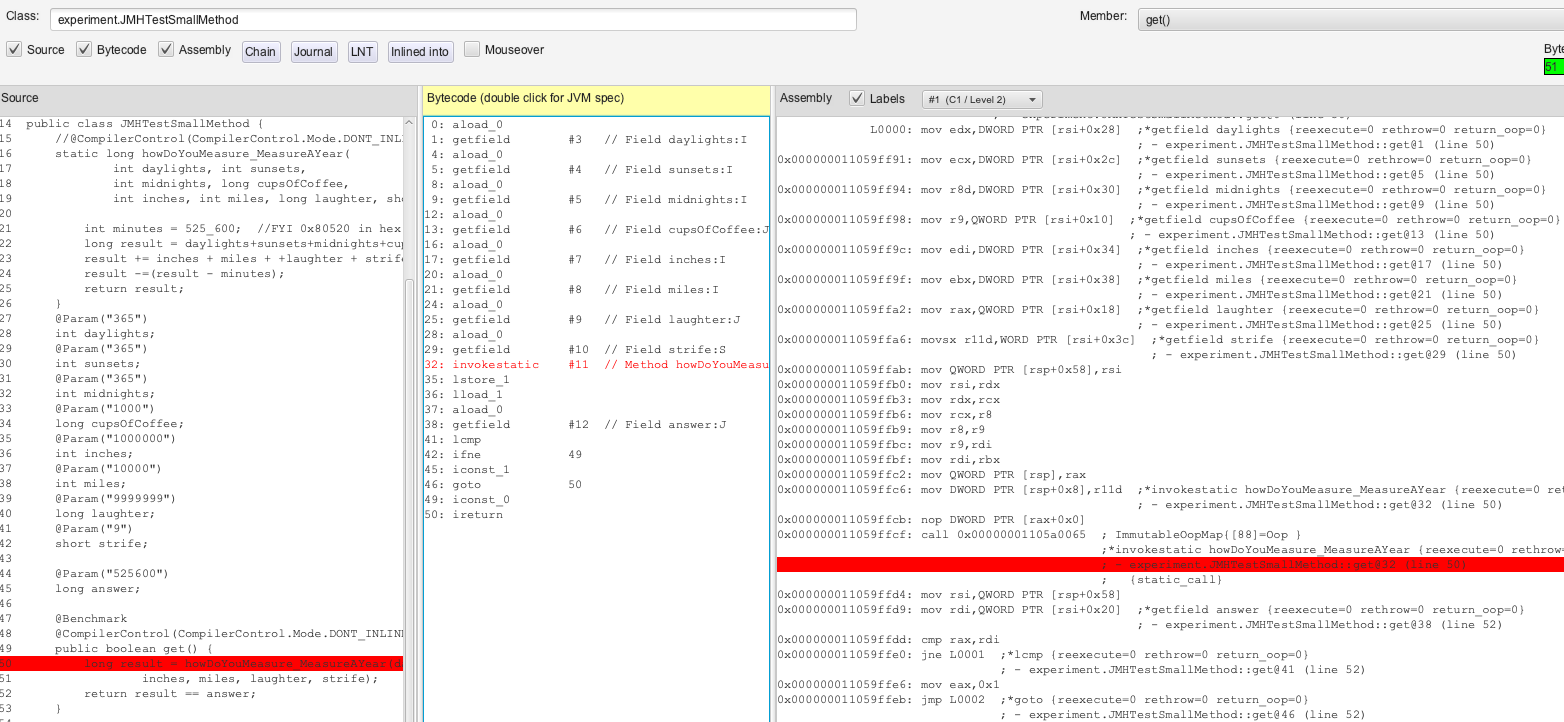

This method always returns 525_600 regardless of input and convoluted logic. The first time that the JIT compiles this to assembler, it will transform the method “as-is”. In JITWatch, we see the following for the get() method, where the code is on the left, the bytecode for the get() method is in the middle, and the assembly on the right:

Figure 2: get() with bytecode and assembly.

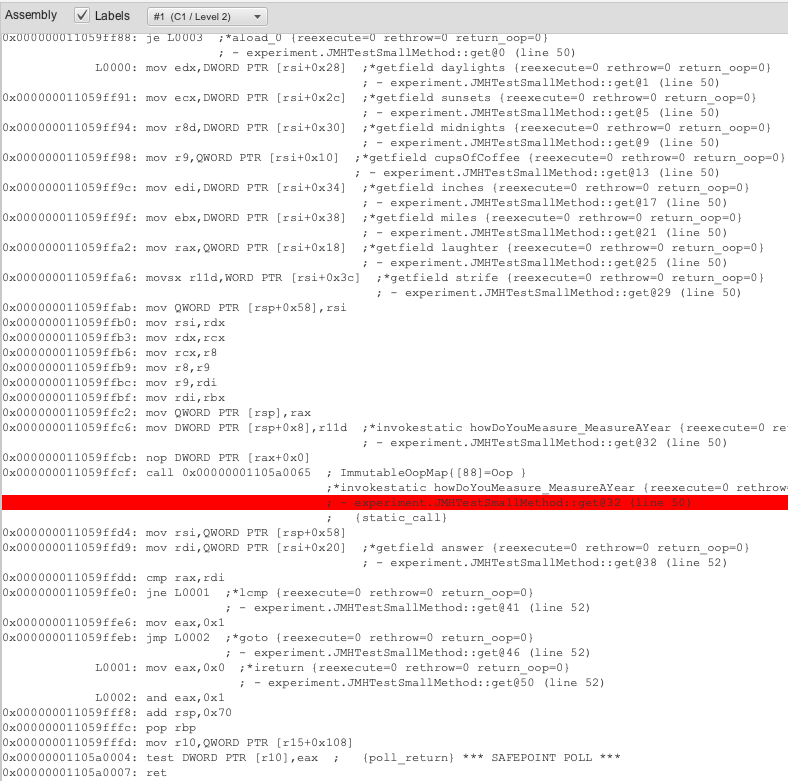

I will zoom in so you can see the assembly better:

Figure 3: C1 get() assembly zoomed

Note all the assembly for gathering member variable data in preparation for the call, as well as the “call” command itself to invoke the child method. In fact, this probably matches your expectations fairly well. Even the variables are in the same order as the code.

The assembly version above is the output of the C1 JIT compiler, which does fast simple-stupid when possible. The assembly for the called method, howDoYouMeasure_MeasureAYear(), is equally straightforward so I’ll skip showing it, but even the pointless additions and subtractions are included.

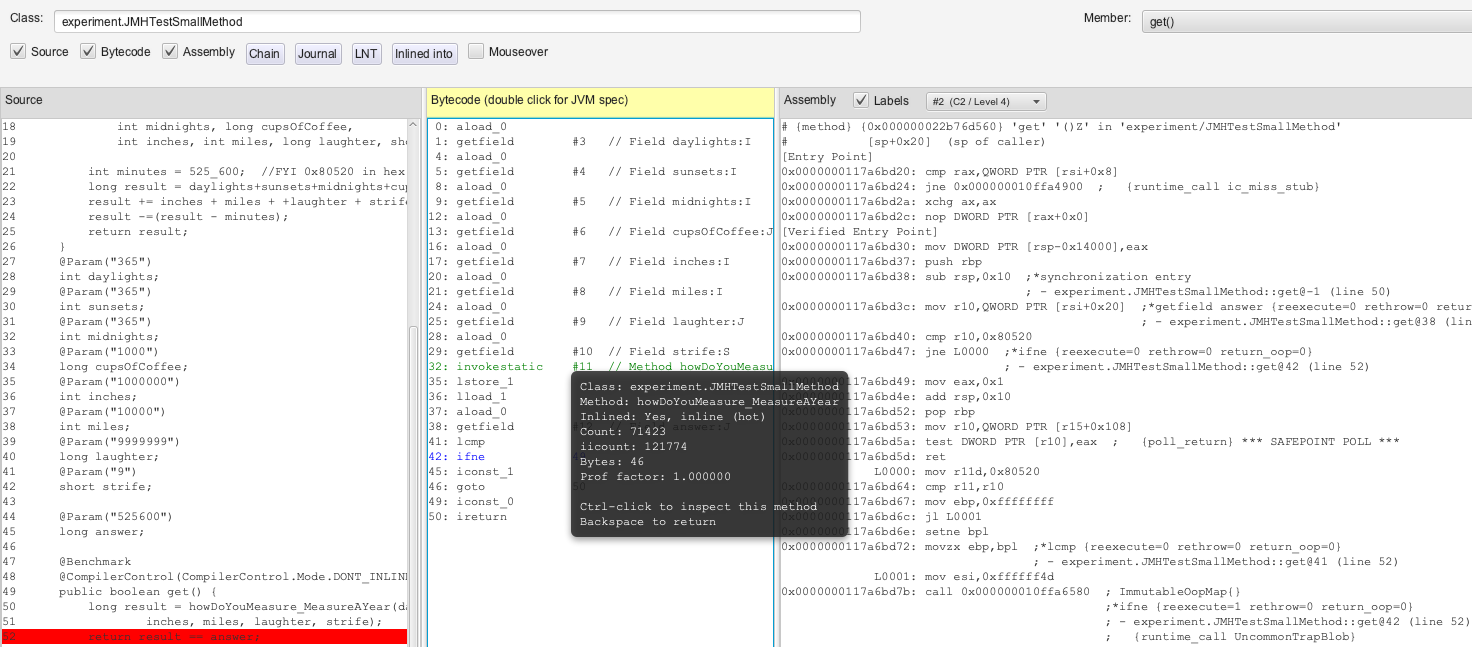

After a few seconds, however, the JIT realizes it has CPU cycles available to take another look. The output of this advanced JIT processor (called the C2) is far more interesting. Now JITWatch shows the following:

Figure 4: get() with optimized assembly

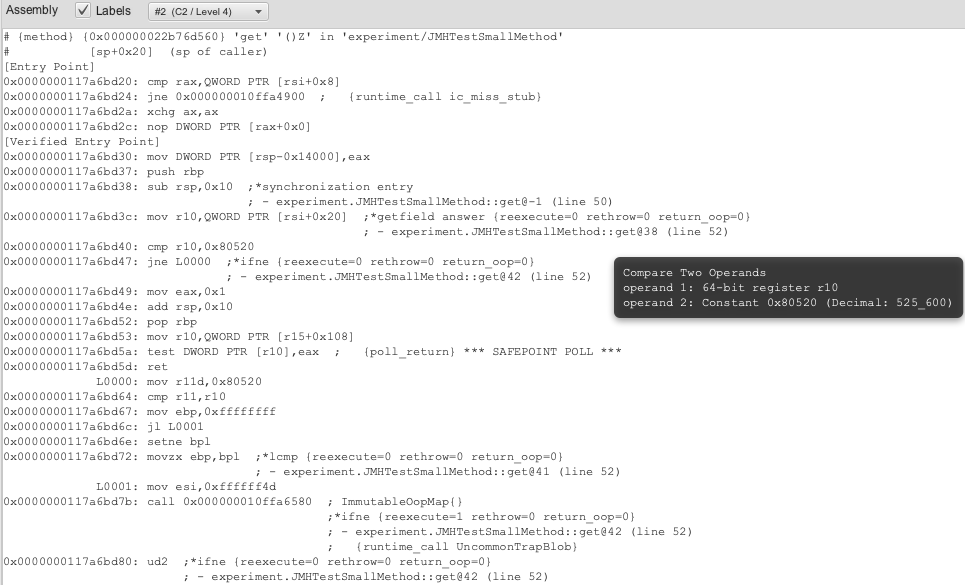

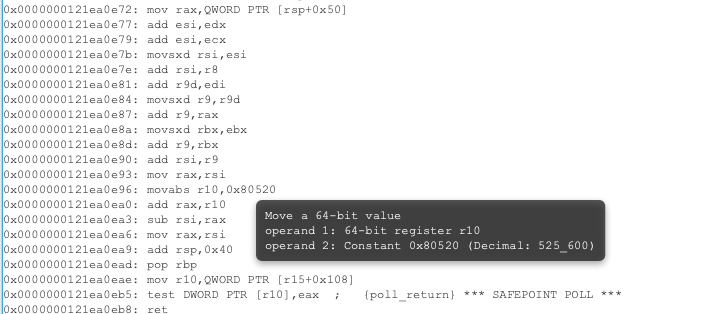

Of course, the java code and the bytecode are still the same. But, the assembly is very different. I will zoom in again:

Figure 5: get() with new optimized assembly zoomed

Now, if you stare long enough at the assembly, you’ll notice several things about this rewrite:

- The JIT is no longer bothering to load member variables into memory in preparation for a call.

- The JIT is actually no longer even calling our child method howDoYouMeasure_MeasureAYear(). It copied the relevant assembly into get() itself.

- This is an optimization called “inlining”, as called out in the popup.

- The JIT has simply put the method result it always gets, 0x80520 (or 525_600 in hex), as a constant for get() to use.

- The JIT simply compares field “answer” and 525_600 in hex and returns 1 (true) if they match.

- If the JIT is ever wrong about field “answer” matching 525_600 in hex, it will abort the optimization and call the original method as its assumptions are no longer valid.

- This is called an “uncommon trap”.

Given all the addition and subtraction operations in the original method, this is a significant rewrite of our code! Here is a portion of the assembly of the original method, all of which has now been removed by the C2:

Figure 6: Original (now removed) assembly of “howDoYouMeasure_MeasureAYear()”

Again, if you try to debug the changes, you will simply step over the unchanged bytecode, not the assembly, and so will never be able to observe it.

If you are curious, a colleague of mine has indeed seen this in production. It was, of course, only through research like the above that the issue was resolved. “Volatile” is definitely on our checklist for spotting errors of omission.

Conclusion

This post was about an infinite loop puzzle, but also much more. As software engineers, we often search for magic incantations (code snippets) from online communities for our immediate problem at hand, enjoy introductory videos for the latest technologies or concepts, and certainly (hopefully) peruse online manuals for the same. However, without studying the software engineering “giants”, you will only learn to solve the issues that you know about. You will miss learning the solutions to all the unknown issues you have yet to encounter, often interweaving concepts you have yet to come across. For me, at the time I was first studying Hawkins, this puzzle was just one such example, and Hawkins was just one of several “giants” introducing me to the vast amount I did not know. Enjoy studying my giants above, or discover your own, and amaze yourself with how much farther you begin to see.

Special thanks to Aleksey Shipilev and Sebastian Neubauer for all the comments and suggestions.

Credit to song Seasons of Love for inspiration for my method.