Dask Usage at Blue Yonder

Back in 2017, Blue Yonder started to look into Dask/Distributed and how we can leverage it to power our machine learning and data pipelines. It’s 2020 now, and we are using it heavily in production for performing machine learning based forecasting and optimization for our customers. Over time, we discovered that the way we are using Dask differs from how it is typically used in the community. (Teaser: For instance, we are running about 500 Dask clusters in total and dynamically scale up and down the number of workers.) So we think it’s time to take a a look at the way we are using Dask!

Use case

First, let’s have a look at the main use case we have for Dask. The use of Dask at Blue Yonder is strongly coupled to the concept of datasets, tabular data stored as Apache Parquet files in blob storage. We use datasets for storing the input data for our computations as well as intermediate results and the final output data served again to our customers. Dask is used in managing/creating this data as well as performing the necessary computations.

Our pipeline consists of downloading data from a relational database into a dataset (we use Dask here for parallelization of the download) and then of several steps that each read the data from an input dataset, do a computations on it, and write it out to another dataset.

In many cases, the layout of the source dataset (the partitioning, i.e., what data resides in which blob) is used for parallelization. This means the algorithms work independently on the individual blobs of the source dataset. Therefore, our respective Dask graphs are embarassingly parallel. The individual nodes perfom the sequential operations of reading in the data from a source dataset blob, doing some computation on it, and writing it out to a target dataset blob. Again, there is a final reduction node writing the target dataset metadata. We typically use Dask’s Delayed interface for these computations.

In between, we have intermediate steps for re-shuffling the data. This works by reading the dataset as a Dask dataframe repartitioning the dataframe using network shuffle, and writing it out again to a dataset.

The size of the data we work on varies strongly depending on the individual customer. The largest ones currently amount to about one billion rows per day. This corresponds to 30 GiB of compressed Parquet data, which is roughly 500 GiB of uncompressed data in memory.

Dask cluster setup at Blue Yonder

We run a somewhat unique setup of Dask clusters that is driven by the specific requirements of our domain. For reasons of data isolation between customers and environment isolation for SaaS applications we run separate Dask clusters per customer and per environment (production, staging, and development).

But it does not stop there. The service we provide to our customers is comprised of several products that build upon each other and maintained by different teams. We typically perform daily batch runs with these products running sequentially in separated environments. For performance reasons, we install the Python packages holding the code needed for the computations on each worker. We do not want to synchronize the dependencies and release cycles of our different products, which means we have to run a separate Dask cluster for each of the steps in the batch run. This results in us operating more than ten Dask clusters per customer and environment, with most of the time, only one of the clusters being active and computing something. While this leads to overhead in terms of administration and hardware resouces, (which we have to mitigate, as outlined below) it also gives us a lot of flexibility. For instance, we can update the software on the cluster of one part of the compute pipeline while another part of the pipeline is computing something on a different cluster.

Some numbers

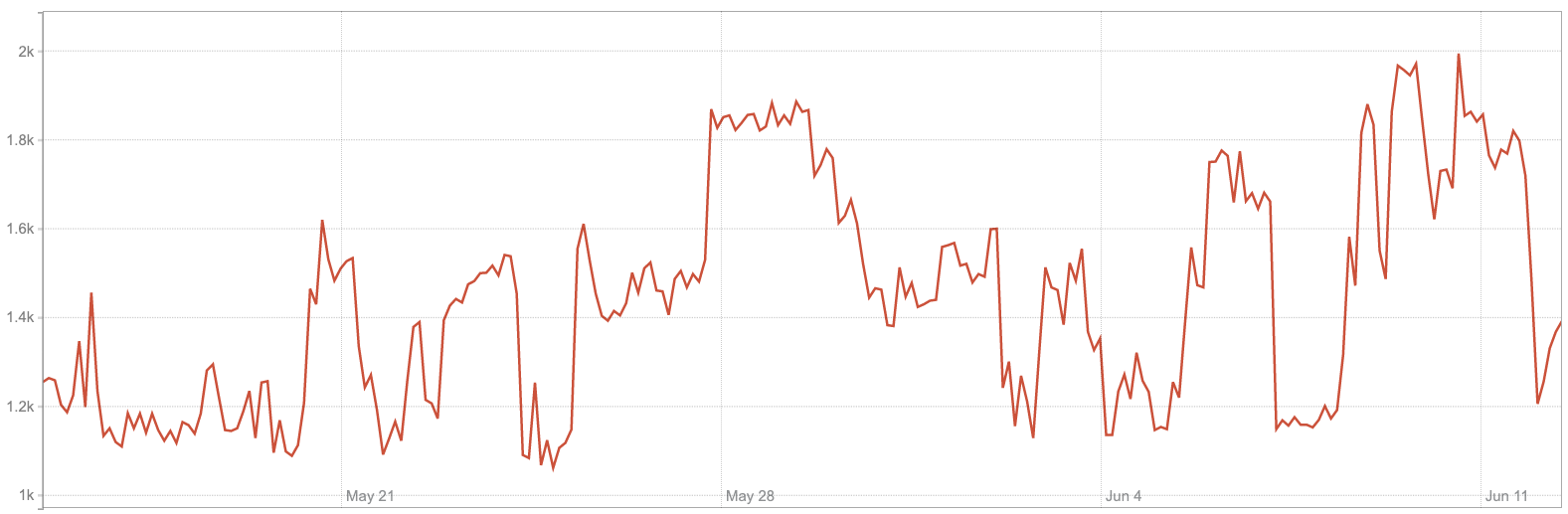

The number and size of the workers varies from cluster to cluster depending on the degree of parallelism of the computation being performed, its resource requirements, and the available timeframe for the computation. At the time of writing, we are running more than 500 distinct clusters. Our clusters have between one and 225 workers, with worker size varying between 1GiB and 64GiB of memory. We typically configure one CPU for the smaller workers and two for the larger ones. While our Python computations do not leverage thread-level parallelism, the Parquet serialization part, which is implemented in C++, can benefit from the additional CPU. Our total memory use (sum over all clusters) goes up to as much as 15TiB. The total number of dask workers we run varies between 1000 and 2000.

Cluster scaling and resilience

To improve manageability, resilience, and resource utilization, we run the Dask clusters on top of Apache Mesos/Aurora and Kubernetes. This means every worker as well as the scheduler and client each run in an isolated container. Communication happens via a simple service mesh implemented via reverse proxies to make the communication endpoints independent of the actual container instance.

Running on top of a system like Mesos or Kubernetes provides us with resilience since a failing worker (for instance, as result of a failing hardware node) can simply be restarted on another node of the system. It also enables us to easily commission or decommission Dask clusters, making the amount of clusters we run manageable in the first place.

Running 500 Dask clusters also requires a lot of hardware. We have put two measures in place to improve the utilization of hardware resources: oversubscription and autoscaling.

Oversubscription

Oversubscription is a feature of Mesos that allows allocating more resources than physically present to services running on the system. This is based on the assumption that not all services exhaust all of their allocated resources at the same time. If the assumption is violated, we prioritize the resouces to the more important ones. We use this to re-purpose the resources allocated for production clusters but not utilized the whole time and use them for development and staging systems.

Autoscaling

Autoscaling is a mechanism we implemented to dynamically adapt the number of workers in a Dask cluster to the load on the cluster. This is possible since Mesos/Kubernetes . This makes it really easy to add or remove worker instances from an existing Dask cluster.

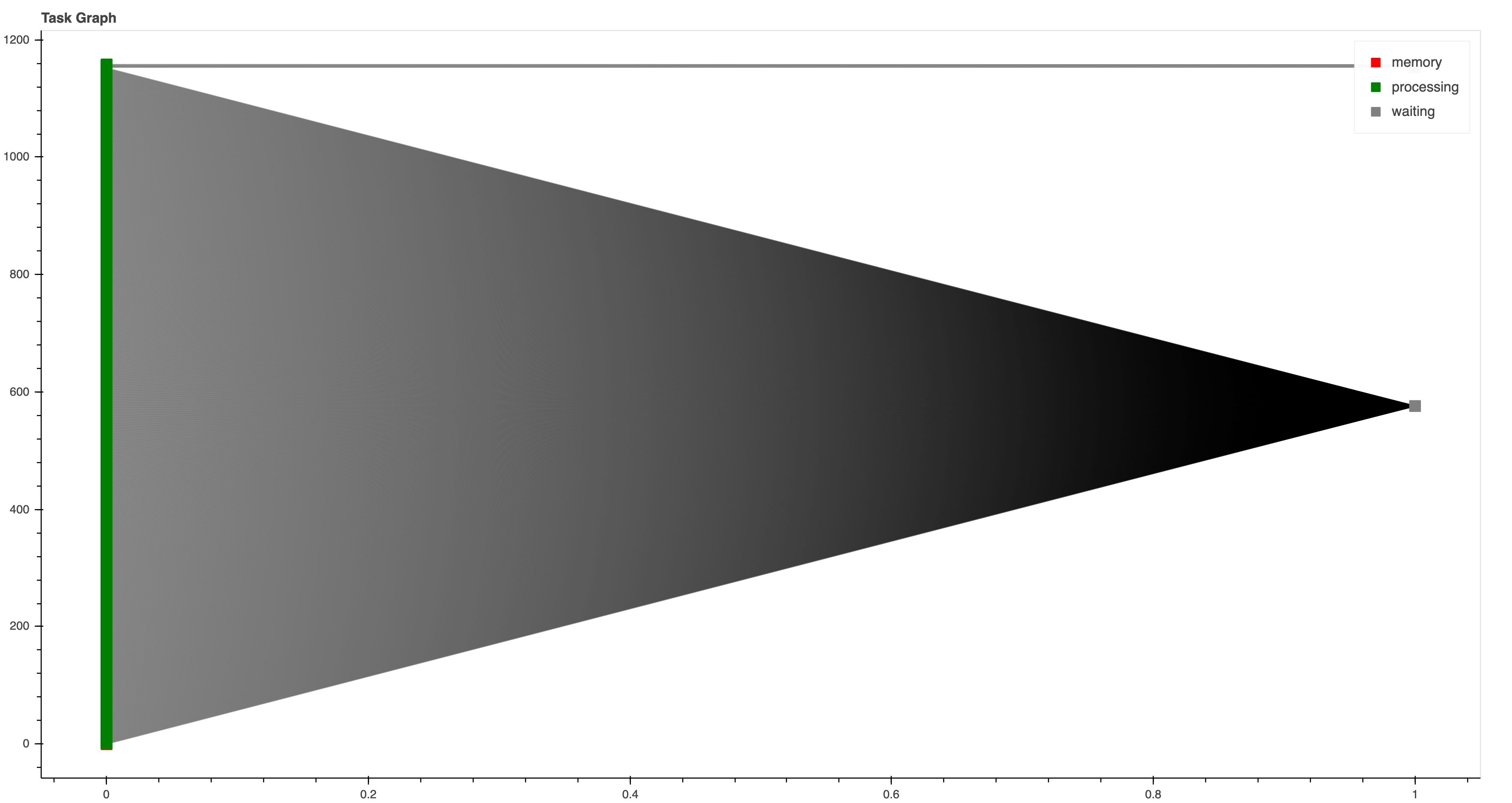

To determine the optimum number of worker instances to run, we added the desired_workers metric to Distributed.

The metric exposes

the degree of parallelism that a computation has and thus allows us to infer how much workers a cluster should

ideally have. Based on this metric, as well as on the overall resources available and on fairness criteria

(remember, we run a lot of Dask/Distributed clusters), we add or remove workers to our clusters.

To resolve the problem of balancing the conflicting requirements for different resouces like RAM or CPUs

using Dominant Resource Fairness.

Dask issues

The particular way we use Dask, especially running it in containers connected by reverse proxies and the fact that we dynamically add/remove workers from a cluster quite frequently for autoscaling has lead us to hit some edge cases and instabilities and given us the chance to contribute some fixes and improvements to Dask. For instance, we were able to improve stability after connection failures or when workers are removed from the cluster.

If you are interested in our contributions to Dask and our commitment to the dask community, please also check out our blog post Karlsruhe to D.C. ― a Dask story.

Conclusion

Overall, we are very happy with Dask and the capabilities it offers. Having migrated to Dask from a proprietary compute framework that was developed within our company, we noticed that we have had similar pain points with both solutions: running into edge cases and robustness issues in daily operations. However, with Dask being an open source solution, we have the confidence that others can also profit from the fixes that we contribute, and that there are problems we don’t run into because other people have already experienced and fixed them.

For the future, we envision adding even more robustness to Dask: Topics like scheduler/worker resilience (that is, surviving the loss of a worker or even the scheduler without losing computation results) and flexible scaling of the cluster are of great interest to us.